The Soviet–Afghan War destroyed Afghanistan and contributed to the dissolution in 1991 of the Soviet Union into 15 republics as well as the liberation of seven European countries. Moscow had been weakened as a result of other costly Cold War misadventures as well as by domestic political stalemate, economic backsliding, and growing ethnic tensions across its vast empire. Collapse came quickly with little violence. Former Soviet republics and seven Central European “satellite” nations, tethered to Moscow by the Warsaw Pact, spun off. Moscow’s Soviet Union became the Russian Federation, shrinking in size from 22.4 million square kilometers to 17 million square kilometers. While still the largest country in the world geographically, Russia now represents only 3.4 percent of the world GDP (slightly less than Japan) and hurtles toward another state collapse. Financially, it is going bust, its military is degraded and disgraced, its reputation ruined, and its European energy customers are now mortal enemies. Internally, alienated ethnic minorities have been disproportionately killed as cannon fodder in Ukraine and dozens of separatist movements grow more rapidly than they did in 1991. Russia hurtles toward collapse.

The issue is not whether Russia will break up, but when and how. Will it become a messy, violent Yugoslavia situation or, more likely, simply fall apart without violence as did the Soviet Union. Some regions, with cohesive societies, will begin to demand more autonomy or simply exit. The most likely candidates to leave will be regions on Russia’s periphery that, like the former Soviet republics, have identities, leaders, and reasonable economic prospects. In 1991, the former Warsaw Pact “satellites” left easily because they were nation-states before they were acquired by the Kremlin after the Second World War. The exit of the 15 former Soviet republics, such as Ukraine, the Baltics, and Central Asia also left easily because they were already semi-autonomous nation-states.

Going forward, Russia’s future construct will be determined by economics, its post-war condition as well as by its leadership. A new regime may keep it together by relaxing controls and sharing the wealth to keep unity, but a post-war Russia may be unable to pull that off. The possibility of outright dissolution sounds far-fetched, but current conditions make this feasible. Few observers would have believed in 1989 that the Soviet Union would disappear and 22 new nations would emerge.

Now, as back then, Russia’s financial situation is dire. Its budget deficit was $47 billion in 2022 and has risen to more than that in the first quarter of 2023. Revenues have collapsed, forcing it to slash services and subsidies to its hinterland. Add to that, Western allies have frozen $300 billion or more of Russian foreign exchange assets that will be earmarked to rebuild Ukraine. Clearly, the center will not hold and Russia, as currently constituted, is likely to unravel, even if the war ends and a new, less suicidal regime replaces Putin’s.

Who will leave first? It’s a safe bet that regions closest to Europe, or in Europe itself, will be able to more easily get out from under Moscow. They have existing ties with the West and neighbors, are close to markets and potential trade partners, have modern infrastructure, and will be able to eventually get into NATO or the European Union. Unfortunately, Russia’s regions in Asia, or those landlocked inside the Federation, will have to join forces to cobble together viable entities and then have to find assistance or form political partnerships with outsiders in the West, Central Asia, or Asia. The challenge is that Russia consists of 190 ethnic minorities spread across 11 time zones whose lives have been governed mostly by Moscow-appointed administrators and whose economies have been dominated by Russian-owned enterprises.

Janusz Bugajski’s book Failed State: A Guide to Russia’s Rupture makes the case that dissolution is inevitable. He is a political scientist with The Jamestown Foundation. And there is an NGO which actively promotes the partition of Russia, called the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum. It is founded by Russian opposition activists, regional and separatist movements in Russia as well as a few foreign sympathizers. Spearheaded by Austrian economist Gunther Fehlinger, it stages conferences to fight for the “decolonization, de-occupation, decentralization, de-Putinization, denazification, and de-militarisation of Russia”. Fehlinger says the world now realizes that it’s unacceptable to “keep Russia alive after what it has done in 2022 and 2023.”

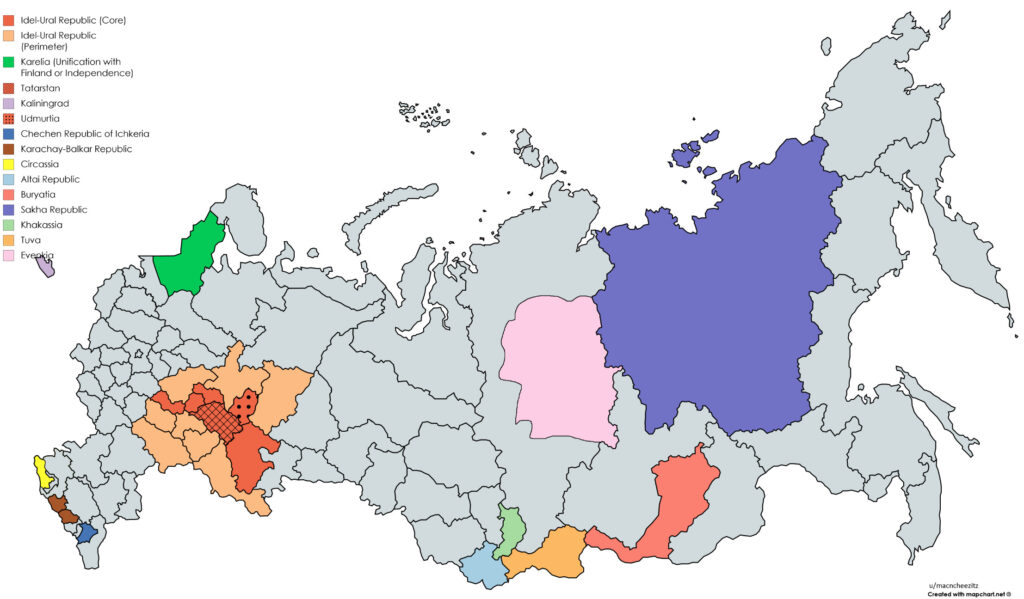

There are dozens of potential new nations but their departure from Russia is far from certain except in several areas. For instance, Karelia is a scenic region in Russia’s northwest corner which Finland was forced to cede to Moscow in 1940. Karelians are a Finnish ethnic group and there remains a political movement in Finland to get it back. Similarly, Estonia and Latvia were forced to cede land to Russia after the Second World War that they would gladly re-acquire. There’s also Kaliningrad, detached from Russia and sandwiched between Lithuania and Poland, which is an ice-free port on the Baltic Sea that was captured by Russia from Germany in 1945. It could become a viable fourth Baltic Republic because its 500,000 inhabitants have an economy the size of Montenegro’s.

Other viable European entities exist in Russia’s southwest territory between the Black and Caspian Seas. Possible candidates include a resurrected version of the North Caucasus Republic, which existed between 1918 and 1922, involving Chechnya and six others. Another possible nation-state is the Ural Republic which was proposed and declared in 1923, but never created. It consisted of 11 regions east of the Ural Mountains. Either entity, if independent now, could be economically viable.

Partition activist Fehlinger suggests that an EU-type alliance, he calls the EAU or EurAsian Union, could be formed with help from Western nations. This is how Brussels helped the Warsaw Pact nations thrive after they left the Soviet Union. He also warns that the West must prepare for this because there will be fierce competition for hegemony over this territory. This “Great Power Competition” is why the West must invest quickly. “Better they [Russian spin-offs] join the ‘Free World’ rather than ‘China World’,” states Fehlinger.

While daunting and challenging, the dismantling of the Russian Federation would be a welcome development. The world would obviously be better off if Moscow’s monstrous dictatorship no longer controlled one-tenth of all the land on Earth and a nuclear arsenal. But the West is not prepared for the possibility of Russia’s disintegration and it must be. This is not preposterous. It is inevitable.

This is a reprint of a Diane Francis article with her permission to republish.